Low temperature preservation of cells, tissues and organs

Course Handbook - Basic version

1. Historical introduction

1.1 Initial experience

Scientific background was laid by A.Carrel in 1912 (Carrel 1912).

The first sources of tissues usable for transplantation were amputated limbs (bones, cartilage and skin) and enucleated eyes (cornea) in that time.

The first total keratoplasty – cornea transplantation in the world was made by E. K. Zirm in Olomouc in 1906, already (Zirm 1906).

Since 1935 also corneas collected in deceased donors have been used for clinical transplantation (Filatov 1935).

After 1945 the spectrum of tissues collected in deceased donors was enlarged and the first multi-tissue banks were established( Klen, Hradec Králové, Czechoslovakia, 1952) (Klen 1952,1957), Hyatt (Bethesda, Maryland, USA 1951) (Hyatt and Wilber 1959).

The first preservation methods were very simple – the tissues were put into the moist chamber – a closed sterile jar or Petri dish with small amount of physiogical saline at the bottom and were stored in a refrigerator at +4°C (Fig.1).

Figure 1 Split pigskin stripes placed on moisted gauze and kept in a moist-chamber – Petri dish with sterile physiological saline at the bottom. Shelf life of grafts was 10 days at +4°C (picture from 1985).

The first monograph "Temperature and Living Matter" summarizing the knowledge on the influence of both high and low temperatures on cells, tissues and organs was written by J. Bělehrádek, professor of biology at the Medical School of the Charles University in Prague (Bělehrádek 1935).

In that time it was believed that achieving vitrification, ie avoidance of crystalization by very fast cooling, was the correct way to achieving good recovery of viable cells after thawing.

The results of experiments that used this methodological approach were summarized by Luyet and Gehenio in their monograph "Life and Death at Low Temperatures" published in 1940. The majority of results were negative, however (Luyet and Gehenio 1940).

1.2 Discovery of the cryoprotective action of glycerol

The breakthrough happened in Cambridge in 1949. Christopher Polge and his co-workers discovered the cryoprotective effect of glycerol when performing experiments with freezing the fowl spermatozoa (Polge et al. 1949).

Glycerol was immediately started to be used in freezing sperm of different domestic animals (Polge and Rawson 1952, Kuznetsov 1956) and later also in freezing of human sperm (Sherman 1954,1957). Glycerol was also successfuly used in freezing of red blood cells (Smith 1950,Tullis 1959), bone marrow (Barnes and Loutit 1955, Pegg and Trotman 1959), skin and tissue culture cells (Taylor and Gerstner 1955, Pomerat and Morehead 1956).

The results of this empirical era of cryobiology were summarized by A. Smith in her monograph "Biological Effect of Freezing and Supercooling" published in 1961 (Smith 1961).

1.3 Dimethylsulphoxide – more efficient cryoprotectant

In 1959 Lovelock and Bishop described the cryoprotective effect of dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO), till now the most efficient cryoprotectant (Lovelock and Bishop 1959). Its advantage was the high penetration rate accross the cell membrane, which made it possible ,to avoid its removal after thawing, that was obligatory in case of glycerol (Fig.2a,b,c).

Figure 2 a,b,c Suspension of peripheral blood progenitor frozen in presence of 15%glycerol in a stainleess-steel container. Container in the freezing chamber of the programmable freezer (a), freezing protocol used (b) and the thawed suspension after deglycerolisation (c) (Pictures from 1989).

DMSO is however toxic and its daily dose must be limited in case of intravenous administration.

In the recent years intensive research has been carried out to find new alternatives meeting the current requirements on the safety and quality of products used for medical applications (Awan 2020).

1.4 Theoretical explanation of the mechanism of the freezing damage and cryoprotection

Theoretical explanation of mechanisms of freezing damage was made by P. Mazur, Oak Ridge National Laboratory,Tenessee, USA in 1963 (Mazur 1963) (Fig.3)

Figure 3 Prof. P. Mazur during his introductory talk at the cryobiological conference held in Hradec Králové in 1992.

Mazur showed that some single-celled micro-organisms, e.g. yeasts, could survive slow cooling by the rate 1K/min and that in using this rate all freezable water crystallized outside cells, the cells dehydrated and shrank and thus escaped from intracellular ice formation, that was proved to be lethal. He was able to describe this process mathematically (Mazur 1963).

This is not, however, a single damaging mechanism, the cells are also damaged by formation of highly concentrated solutions formed after primary crystallization, i.e. crystalization of water was completed (solution effect).

The addition of a penetrating cryoprotectant, such as of glycerol or DMSO leads to lowering of the salt concetration and thus prevents the excessive cell dehydration.

The mechanism of action of extracellular macromolecular cryoprotectants, such as dextran or hydroxyethylstarch is less clear, these cryoprotectants inhibit crystal growth, protect cell mebranes and bind a substantial amount of water ouside cells which again avoids excessive cell dehydration (Sputtek et al.1 990).

In the middle of the 60 s Harold T. Meryman summarized the existing knowledge of the cryobiological theory and its applications in his monograph "Cryobiology" (Meryman 1966)

Scientific societies Society for Cryobiology and Society for Low Temperature Biology were established in 1964.

Blood banks oriented to long-term storage at deep subzero temperatures have become standard part of the transfusion service ( Rowe 1971, Sumida 1974).

Since the late seventies of the last century there has been a rapid development of cryopreservation of haematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) derived from bone marrow, peripheral blood of cord blood ( Scheiwe et al 1981, Stiff et al 1987, Gluckmann et al 1989, Měřička 1991, Hunt 1996).

The use of cryopreservation methods in human reproduction has rapidly expanded as well (Stanic et al. 2000, Payntner 2000, Edgar et al. 2000, Gianarolli et al. 2000).

Cryopreservation of cultured cells used for transplantation, such as keratinocytes usable in treatment of burns (Rheinwald and Green 1977,Gallico et al. 1984, Konigová et al.1989, Brychta et al.1995,Kostadinow et al. 1991, Straková et al. 1995, Klein et al. 1997, Měřička et al. 1996-97)) and of chondrocytes used in treatment of articular cartilage defects was also started (Rendal-Vasquez et al. 2001) .

In the recent years the new societies and working groups have emerged oriented to research of organ cryopreservation – Organ Preservation Alliance (Giwa et al 2017).

1.5 Renaissance of the vitrification approach

Since the 80´s of the last century renaissance of the vitrification, ie. transformation of liquid water into a glass instead of crystalline ice during cooling has taken place.

While Luyet and his coworkers tried to achieve vitrification by using ultra-rapid cooling rates (Luyet and Gehenio 1940), Fahy and his team concentrated their effort on developping of vitrification solutions which replace a part of water in the organ and thus make it possible to achieve vitrification at lower cooling rates (Fahy et al 1987, 2009).

A considerable contribution to development of vitrification procedures was the dicscovery of new compounds enhancing vitrification, 1,2-propanediol or 2,3-butanediol by Pierre Boutron (Boutron 1990). (Fig.4)

Figure 4. Prof. P. Boutron (right) during disscussion at the same conference.

Similar concept was used also by the group of David Pegg (Pegg 1989) in vitrification of tissues, such as corneas or vascular grafts ( Wustemann et al. 2002) and by the research group of Kevin Brockbank in preservation of heart valves and vessels (Song et al 2000).

The great advantage of the vitrification approach is avoidance of damage caused by cryoconcentration of intracelllular and extracellular solutions and of the volume expansion caused by crystalization.

While the progress in methods of achieving vitrification is evident, much less succcessfull is the research of finding optimal warming conditions of the vitrified tissues and organs.

During warming and soon after it tissues and organs may be damaged by highly concentrated toxic cryoprotective agents necessary for achieving vitrification.

The devitrification (crystalization) processes that may occur during warming may lead to ruptures of preserved tissues and organs (Pegg, Wusteman and Boylan 1997, Felmer et al. 2013, Taylor et al 2019). For this reason some tissue establishments, including ours still prefer using slow cooling protocols in freezing some types of tissues (Mueller-Schweinitzer 2009, Jashari et al 2013, Špaček et al. 2019).

1.6 Low temperature organ preservation

Since the beginning of organ transplantation programes in the late 50's of the last century, the organs have been cold stored after intial perfusion of an explanted organ or after in-situ perfusion of several organs in case of multiple organ harvest in brain-death (Fig. 5a) or non-heart beating donors (Karow et al 1974, Talbot and D Alessandro 2009)

Fig. 5a The organ harvest team during in situ multi-organ perfusion in a brain-death donor.

1.6.1 Organ cold storage

Different organ perfusion solutions suitable for multiorgan perfusion or optimized for perfusion of a particular organ have been developped (Clerk et al 1973, Karow et al. 1974, Talbot and D'Alessandro 2009). The Fig 5b (left) shows the paper boxes with the organ perfusion solution Custodiol CE stored in a refrigerator at +2 till +8°C and the Fig. 5c (right) shows sterile ice stored at high subzero temperature near zero.

Fig. 5 b, c The paper boxes with the organ perfusion solution Custodiol CE in plastic bags are stored in a refrigerator – left, sterile ice (frozen physiological saline in bags) used for making ice slush is stored in a freezer at high subzero temperature - right.

Explanted organs are put into the ice slush Fig. 7 a and b.

Fig.7 a, b Explanted heart (left) and explanted liver (right) in the ice slush.

After initial perfusion the organs are wrapped into sterile plastic bags containing cold perfusion solution . The bags are placed into the plastic or polystyrene insulation boxes (Fig. 8,9). The insulation boxes are filled with the melting ice from the flake ice machine (Fig.10,11)

Fig. 8, 9 Explanted kidney in the plastic bag with sterile perfusion solution inside (left) and explanted lung wrapped in plastic bags and cooled by melting ice (right).

Fig. 10, 11 Flake ice machine (left). Ice flakes are kept at temperature near zero (right)

Temperature record of storage conditions is presented in the Fig 12.

Fig. 12, 13 Temperature record from validation of storage of kidney in a box filled with melting flake ice. The violet line – temperature of ice, the green line temperature of air above ice. A relative stable temperature was maintained for 48 hours (left). Most of kidneys are transplanted within 24 hours in the Czech Republic.

Polystyrene insulation boxes for transport of organs (right) are being exchanged among the transplantation centres.

1.6.2 Continuous perfusion of kidneys

Continuous hypothermic organ perfusion has been used as an alternative of the cold storage since the late 60 s with continuously improving perfusion machines (Grundman et al. 1972, Karow et al. 1974). The Fig 14 shows kidney perfusion with UW solution using the machine RCM 3 Waters ,USA.

Fig. 14 Continuous kidney perfusion on the RMC 3 machine Waters, USA .

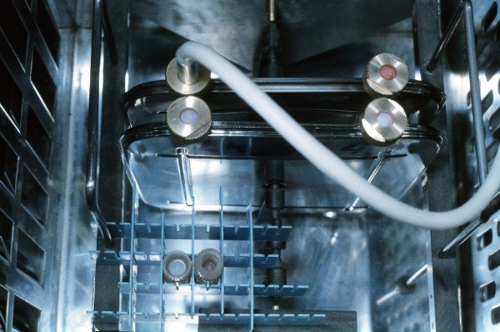

Perfusion is performed in a sterile disposable perfusion chamber (Fig. 15) and kidneys are connected with the organ by special stainless- steel clamps (Fig. 16).

Fig. 15, 16 Sterile disposable perfusion chamber and sensors (blue color) for monitoring perfusion flow parameters (left) and the kidneys connected to the tubing of the perfusion chamber with sterilized stainless steel clamps – picture was taken at the beginning of the perfusion (right).

The screen with displayed data of monitored parameters is shown in the Fig. 17. As continuous perfusion can be used as a tool of the organ viability assessement its use is important especially in organs harvested in marginal and non heart beating donors.The Fig. 18 shows the record from the perfusion of the kidney collected in a marginal brain-death donor. At the begining of perfusion the high renal resistence (red line) and low flow (blue line) was observed. After addition of Verapamil to the perfusion solution the resistance decreased and the flow was normalized.

Fig. 17, 18 Displayed perfusion parameters during continuous hypothermic perfusion of the left kidney – pulse rate (55/min), temperature,of the perfusate (+4.6°C) systolic, diastolic and mean pressure (44-35-31 torr ), flow 45ml/min. and renal resistence 0,57 (left). The record of the continuous kidney perfusion harvested in a marginal donor (right). Yellow and green lines – systolic, diastolic and mean pressure, blue line - flow, red line –renal resistance.

The Fig.19 shows the perfused kidney after disconnection from the machine and the Fig 20 the same kidney after restoration of blood circulation.

Fig. 19, 20 The appearance of the well perfused kidney after continuous perfusion (left)– note the pale colour of the kidney in comparison with the Fig. 16 and the change of the colour of the kidney after restoration of the blood circulation (right).